THE FABRICATOR

July 2017 – By Tim Heston

Millie Ramirez sat looking, analyzing the print. There had to be a better way to form this part. She jumped online, pored over press brake tooling resources, and began sketching.

Then she walked over to the machining department, showed her drawing, and discussed ways in which a custom tool could be milled, turned, and wire electrical discharge machined. The machinist made the tool, then gave it back to Ramirez for testing, who later returned to the machine shop to request modifications. Once the tool was perfected, she worked with engineering to develop the operation and setup sheets, and finally trained staff on how to set up and operate the new press brake tool.

This isn’t entirely unusual for a shop supervisor in metal fabrication, at least in companies that employ people with engineering and toolmaking expertise. Thing is, Ramirez’s situation isn’t typical. She’s 23 years old, and she works on a shop floor that employs more women than men.

Pete Egan, human resources director, didn’t intend to hire more women than men. The women, all of whom came from local technical schools, just happened to be more qualified.

Employing so many young people was a strategy borne out of necessity. Starting about four years ago, Egan realized that the company’s home of Cromwell, Conn., didn’t have enough local, experienced talent to support needed growth. So, he reached out to community colleges, offered internships, and looked for ways to grow the talent. Ramirez came to Carey as an intern in 2015, and upon graduation she became the principal point person for the company’s new venture in sheet metal fabrication.

How has Carey Mfg. navigated the skilled labor issue so effectively? Like any complex puzzle, the effort involved many pieces, including timing, talent, and technology. But much of it boils down to a simple concept: offering opportunity.

Jack Carey graduated from college in 1978, finished an apprenticeship at Pratt & Whitney, and in 1981 struck out on his own to launch Carey Mfg. Inc. in an 800-square-foot facility. It began as a job shop with a manual knee mill and a 5-ton punch press, though soon enough, aerospace machining jobs started coming in the door. But thinking long term, Carey felt that relying solely on job shop work wouldn’t provide much in the way of stability. He soon landed some stamping work, then decided to launch his own product line in 1985, stamping hardware components like latches and catches.

“We invested a lot of time and effort into developing our product line,” Carey said, “because we felt that was the more financially secure route to go.”

In 1986 family friend Ed Floyd approached Carey about going into partnership for a machine shop called Floyd Manufacturing—and with that, a longtime, close business relationship was formed. Carey Mfg. continued its focus on its hardware product lines, while Floyd exited aerospace, which changed significantly after the Cold War ended, and began to concentrate on the automotive market.

Floyd had a good run in the 1990s, but later in the decade Carey thought automotive had run its course; it was time to get back into more defense work. But Floyd wanted to continue with automotive. “I was totally fine with that,” Carey recalled. “I told him that he may well be right, but I didn’t want to be part of it.”

The two ended the business partnership in the late 1990s, and Carey focused solely on his hardware business. Eventually he bought Amatom Mfg. Co., diversifying into electronic equipment hardware.

Then came the recession of 2001. General Motors business went downhill, which eventually drove Floyd Mfg. into bankruptcy. In 2006 Jack Carey partnered again with Ed Floyd and brought his operation into the Carey facility, where the two organizations could share resources. Today the Floyd Mfg. side of the business (mainly a machining operation) has taken off with the automotive sector.

Meanwhile, Carey Mfg. changed dramatically. By 2000 it was cheaper to buy door hardware in China than to stamp it stateside. To stay competitive, Carey had no choice but to stop stamping hardware in-house and start importing products from overseas.

“The cost differential was so great,” Carey recalled. “It cost us a dollar here to make it, but we could buy it from Asia for 35 cents. But over the past two years, that differential has narrowed significantly. Now we compete directly with mild steel products, and we actually beat them pricewise on all stainless products.”

“We tell our customers that we can make anything in our catalog,” said Paul Lavoie, head of marketing and business development. “But if there’s something else you want us to look at, give us the prints. In the hardware business, we serve multiple verticals, from construction to aerospace.”

Carey, a wry New Englander to the core, quipped, “Yeah, sometimes we go diagonal too.”

It still makes sense to order thousands or millions of stamped hardware from Asia, but that’s not what Carey’s customers are demanding. They’re now ordering products in lower quantities, and many are custom. This meant it no longer made sense to make a dedicated stamping tool. Here, laser cutting, punching, and press brake forming fill a need.

A little less than two years ago, Carey was in a position to set the company apart from the competition in the hardware market, where most players still imported products from overseas. Thanks to Floyd Mfg. and its success in the automotive market, as well as the design work associated with the Amatom brand, Carey Mfg. could turn to engineers on staff to develop tooling and design hardware to order.

“If you try to break into this market and you’re just a distributor and have no manufacturing expertise, you need to not only invest in machinery, but you need to ramp up inspection, quality, and engineering,” Carey said. “It’s really cost-prohibitive to do that. For us, we purchased a few machines, and we went to work.”

Specifically, the company purchased several press brakes, a CO2 laser/punch combination machine, and a solid-state fiber-optic laser, all from TRUMPF, along with a nitrogen-generation system.

The 4-kW solid-state laser has helped Carey’s throughput significantly, especially considering the dense nests the operation cuts. “We may put 2,000 parts on a 4- by 8-foot sheet,” Carey said, adding that the operation also highly utilizes form tools on the punch. In most instances, considering how many small parts Carey processes, the more forming the company can do on the punch, the better.

When Carey buys a machine, he starts with the largest version that makes sense for the business, then subsequently purchases smaller versions of the same machine. For instance, he started with a 150-ton press brake with a 15-in. open height and a 10-ft. bed—a large working space for a hardware manufacturer. A small machine would have seemed more “right sized,” but the last thing Carey wanted was to invest in a small machine only to have a forming job come up that had to be outsourced because it was beyond the brake’s capacity.

In early June the company installed a small electric press brake. That small machine now can be used for many small parts, should the larger brake be needed to form larger workpieces.

This strategy also gives the people at Carey, both engineers and shop floor personnel, a larger creative palette to solve customer problems. And it is here where Ramirez steps into the story.

Ramirez remembers her godfather’s machine shop in Puerto Rico. “She was essentially raised in the shop culture,” said Egan.

As Ramirez recalled, “My godfather used to make surgical knives in Puerto Rico. And he decided to teach me. We had both CNC machining and manual machining. I was amazed. I just thought it was all so interesting.”

She came to the U.S. in 2007, attended A.I. Prince Technical High School in Hartford, Conn., then Asnuntuck Community College’s manufacturing program. “That school tends to be at the forefront of Connecticut community colleges, as far as their manufacturing program goes,” Egan said. “We developed an internship program with them, where students would come work for us for 16 weeks, for a couple days a week. And Millie was sent here as an intern. We saw that she was extraordinarily bright. As soon as her internship ran out and she graduated, we hired her.”

“She essentially runs the whole company in the sheet metal area,” Carey said. “She’s our programmer. She runs the lasers, the punch, the brake. She works with our engineers to get the designs right. She builds prototypes. She does the whole thing. Now we’re bringing in additional people, and she’s training them.”

“When I first came here, I just fell in love with the company,” Ramirez said. “As soon as I finished my internship, I remember I was driving them crazy, asking if I could come over and work as a full-time employee.”

“It’s uncanny, but when you look at our workforce, we have either the very old or the very young,” Carey continued, adding that most of the industry veterans work on the milling, turning, and wire EDM side of the business, while young people dominate the sheet metal shop. “Most of our young workers are younger than 25. And regarding all the new sheet metal technology we’ve brought in, only the young people run it.”

So how does Ramirez train the young people coming onboard? She simplifies things as much as she can. On the press brake, for instance, she developed standard practices as to where to place tooling and labels and stores tools based on the jobs they’re used for—this product (say, “Lever 2000” series) goes with that set of tools (also named “Lever 2000”) and that machine program (again, labeled “Lever 2000”).

“Everything is hands-on,” she said. “If I don’t show them how and where to place the tooling on the machine itself, I cannot help them learn.”

Ramirez started as an intern in 2015, and within two years rose to become production supervisor managing eight people in the sheet metal shop.

“It’s really a collaboration,” Carey added. “Everybody knows what they’re doing, but she’s the linchpin that makes everything else work.”

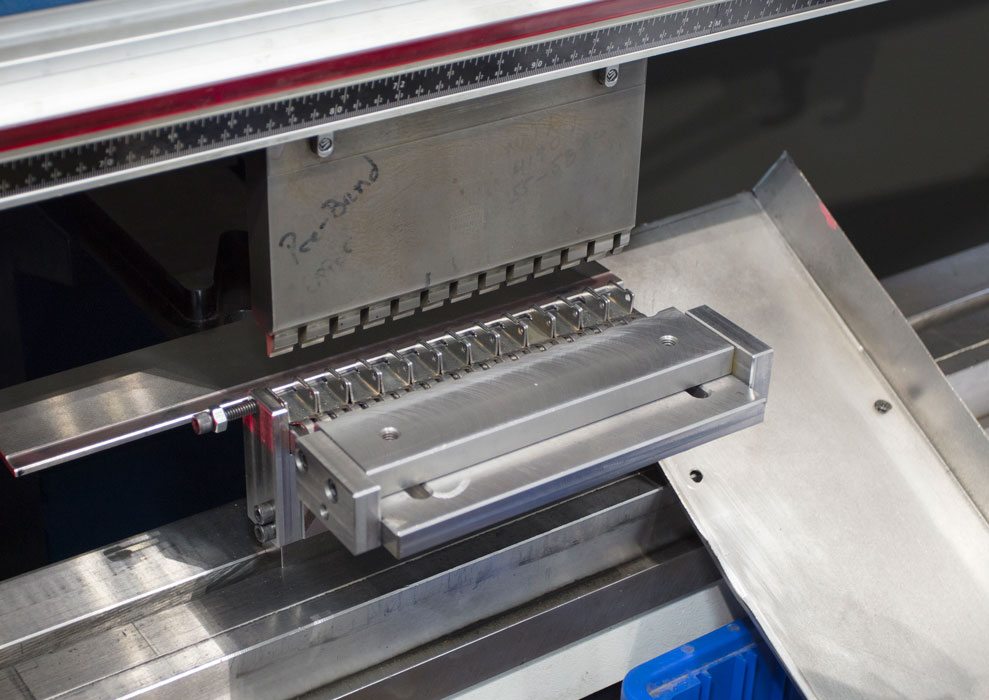

Look at Carey’s press brakes in action, and you don’t find typical straight punches and dies. “We’re adapting these machines to make parts that are not typical for this equipment,” Carey said. “It’s been a real game-changer for us.”

The company has built custom, modular tooling for many of its products, including one that can hold and bend many small workpieces at the same time. Holding the small parts is a flat die with supports that rotate as the punch descends. Another tool has a unique punch with machined pockets and a die fixture designed to hold multiple handles. After the ram cycles, an ejector pushes the formed parts out toward a chute that’s adjacent to the tool set.

As with other tools, Ramirez was central to its development. “I got together with everyone here, and we shared and combined ideas until we came up with a way to put the shape of the handles in the tooling itself,” she said. “We then went over to the EDM machine, we cut it out, tried it out, then kept making modifications until it worked.”

The press brakes also do some forming work for Floyd Mfg.’s automotive customers. For instance, one stick shift part, made of 0.400-in. cold-rolled round stock with threaded surfaces, is bent to a compound angle with a special tool and backgauge setup. The custom die not only fixtures the workpiece in place, but also encapsulates the threads during forming to prevent cracking. The ram speed is also fine-tuned during the forming portion of the stroke.

“We were able to maneuver the machine and make the metal work for us,” Carey said.

In the coming years Ramirez hopes to go back to college. “My hope is to become an engineer in this company and grow more as a person.”

Many shop owners would dream to have a 20-something on staff with such aspiration. So how exactly did she find success? After all, although she did have a strong manufacturing education, both in high school and at the community college, it was generalized. When she arrived at Carey, she knew little about sheet metal fabrication. So how exactly did she hit the ground running at Carey?

Lavoie attributed a lot of it to her background, growing up in a shop environment, and the strong fundamentals taught at the area’s technical schools. But he also attributed it to the culture at Carey, a small company with 37 employees, as well as another 42 on the Floyd Mfg. side of the business.

“It’s all about the expectation you set for people, and the environment that you create when they come to work,” Lavoie said.

The buck stops at Carey himself, but decision-making and authority are pushed down to the front lines. People are given opportunities to think and spread ideas. They’re not just a warm body standing by a machine.

“We now get some of the top picks coming out of the local community colleges and certificate programs,” Egan said. “We’ve developed a trust here, and that’s thanks to people like Millie, Patricia Cancho [in quality control], and a number of others who have come in here. They found success, are moving up fast, and speak well of us.”

Over the next few years Carey will be on the hunt for new talent, particularly as more personnel retire on the machining side. “Finding talent that can carry on the expertise of our experienced machinists—that’s the next step for us,” Carey said.

“We just don’t say no,” Lavoie added. “We have great relationships with the Department of Labor and the related agencies. We get involved, sit on panels. And anytime people want a tour, we say yes. By doing all that, we uncover opportunities.”

Images courtesy of TRUMPF Inc. , 860-255-6000, http://www.us.trumpf.com